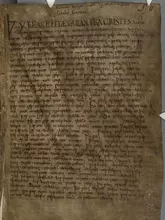

Cambridge Corpus Christi College MS 173, fol. 1r (wikicommons)

The A-Text, sometimes referred to as the Parker Chronicle, is the oldest extant version of a group of texts known since the nineteenth-century as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle(s). Six chronicle manuscripts of various lengths have survived in Old English, familiarly known by their sigla, A–E (F, a Latin translation, was made at Canterbury in the twelfth century, and G, an early copy of A, was heavily damaged in the Cotton fire of 1731). Recently, there has been a move to retitle them as the ‘Old English Chronicles’ to reflect the language in which they were written. The A-text survives in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge 173, a manuscript long associated with the West Saxon King Alfred (acc. 871, d. 899), although there is no evidence that the king himself was involved in its production. That said, the script of the A-text’s main hand (up to 891), dated to the end of the ninth or the beginning of the tenth century (ix/x), has suggested to many that the writing of the Chronicle was associated with Alfred’s court. Indeed, the greatest part of the common stock, that portion of the Chronicle, whose entries extend to c. 892 and are shared among texts A-E, is primarily interested in the reign of Alfred and the West-Saxon royal line. Asser, the Welsh bishop who was for a time at Alfred’s court, used a version of the common stock for the years 851 to 887 for his Latin Life of King Alfred.

In CCCC 173, the A-text is prefaced by a genealogy of the West-Saxon kings extending to King Alfred. Thereafter the Chronicle begins with an entry for 60 BCE noting Julius Caesar’s expedition to Britain, followed by ‘AN I’ (1 CE) with the birth of Christ. Entries are headed by the abbreviation AN (for Latin ‘anno’, ‘in the year’) before the date, and the Old English word ‘Her’ (‘here’ for ‘in this year’) begins each entry. (Some entries in the continuations depart from this practice). Most of the A-text in its early years comprises sparse, disconnected entries on early Christian world history. But entries become more regular with the annal for 449, the coming to Britain by peoples led by two Germanic chieftains, named ‘Hengest’ and ‘Horsa’. Amid the entries chronicling British losses are annals beginning in 495 where Cerdic, the founder to whom the kings of Wessex traced their lineage, arrived in England.

The interest of the common stock in the invasions of the First Viking Age (c. 780–900) and its fullest entries develop prominently with the accession of King Æthelwulf (Alfred’s father) to the West Saxon throne in 836, and, after his death in 855, with the succession of his sons. The Chronicle recounts the precarious situation of Wessex after the capitulation of Northumbria and East Anglia and the difficult campaigns of 871 during which year Alfred succeeds his brother King Æthelred. By 878, Wessex is all but defeated as the king retreats to swampland in Somerset:

Her hiene bestæl se here on midne winter ofer tuelftan niht to Cippanhamme ond geridon Wesseaxna lond ond gesæton ond micel .æs fol ces ofer sæ adræfdon, ond þæs oþres þone mæstan dæl hie geridon, ond him to gecirdon buton þam cyninge Ælfrede, ond he lytle werede unieþelice æfter wudum for ond on morfæstenum. Ond þæs ilcan wintra wæs Inwæres broþur ond Healfdenes on Westseaxum on Defenascire mid xxiii scipum, ond hiene mon þær ofslog ond dcccmonna mid him ond xl monna his heres. Ond þæs on Eastron worhte Ælfred cyning lytle werede geweorc æt Æþelingaeigge. Ond of þam geweorce was winnende wiþ þone here ond Sumursætna se dæl, se þær niehst wæs.

[In this year in midwinter after Twelfth Night the army stole away to Chippenham and rode all over the land of the West Saxons and occupied it, driving many of the population across the sea, and subduing the greatest part of the others, and these submitted to them, except for King Alfred, and he with a small band of men moved around with difficulty through woods and inaccessible marshland. And that same winter a brother of Inwær and Healfdene arrived in Wessex, in Devon, with twenty-three ships, and he was killed there, and eight hundred men with him, and forty other men of his army. And the following Easter, King Alfred, accompanied by a small band of men, built a fortification at Athelney, and from that fortification, he, with that part of the people of Somerset that lived nearest, proceeded to fight against the army.] (Bately, ed. and trans., The Old English Chronicle, volume 1, The A-Text to 1001, pp. 94–95; hereafter cited by page numbers).

Easter brought a stunning change for the English, and Alfred, having put to flight the Danish army, received the Danish King Guthrum and 30 prominent men, in baptism. Subsequent annals through 891 trace the continuing depredations of the Danes both in England and on the Continent amid the king’s efforts to secure Wessex.

Although there is disagreement on which entry ends the common stock (and thus how to classify the annals for 890 and 891), the entries between 893 and 896, known as the first continuation, substantially complete the account of the events of the reign of King Alfred. The entries from 897 to 914 constitute the second continuation, dealing with events of the reign of Alfred’s son, Edward the Elder. A third continuation in A for events from 915 to 920 is not shared by other Chronicle texts. Following this third continuation, the entries in A until 1001 (where the Old English A breaks off), are generally brief, with some entries in verse.

Chronicles group their materials by specific years and lack the narrative sweep of what we would call ‘history’. From basic recording of accessions, consecrations, deaths, and battles, the A-text also includes denser entries following the changing fortunes of the English as the Danish armies move back and forth to the Continent. But while the lengthy entries in the first continuation may suggest a single perspective, the A-text only rarely transcends the limitations of Chronicle. Where it does, the contrast is striking.

The entry for 755 (=757) recounts the events leading up to the murder of the West-Saxon King Cynewulf by Cyneheard, a claimant to the throne. That its material is proper to 784 suggests that it was added as a separate piece during the writing of the Chronicle. Its central interests are right action, loyalty to one’s lord, and vengeance. Following the killing of the king and his small retinue, Cynewulf’s full retinue arrives and besieges Cyneheard and his men. In the context of the Chronicle, the balance of the narrative and its detail are extraordinary, including a rare instance of direct address, as Cyneheard and his men choose death at the hands of the king’s avengers:

Ond þa budon hie hiera mægum þæt hie gesunde from eodon. Ond hie cuædon þæt tæt ilce hiera geferum geboden wære þe ær mid þam cyninge wærun. Þa cuædon hie þæt hie hie þæs ne onmunden ‘þon ma þe eowre geferan þe mid þam cyninge ofslægene wærun’. Ond hie þa ymb þa gatu feohtende wæron oþ þæt hie þærinne fulgon ond þone æþeling ofslogon ond þa men þe him mid wærun […].

[And then they offered their kinsmen the chance to go away unharmed. And the ætheling’s men replied that the same had been offered to their own companions who had previously been with the king. And they said they did not consider this for themselves ‘any more than your companions who were killed with the king’. Then they kept on fighting around the gates until the king’s men forced their way in and killed the ætheling and the men that were with him […].] (pp. 58–9)

The spare entries after 920 are supplemented by four poems (for the annal years 937, 942, 973, 975) in ‘classical’ old English verse, the most famous of which is the ‘Battle of Brunanburh’, although the actual site of the battle is unknown. But these later entries of the A-Text are far from the records of struggle and triumph in the reigns of Alfred and his son. The last entry in A from Anglo-Saxon England foreshadows the disaster to come in the eleventh century:

And hy ðær aflymede wurdon, and ðær wearð fela ofslegenra, and ða Denescean ahtan wælstowe geweald and ðæs on mergen forbærndon þone ham æt Peonho and æt Glistune, and eac fela godra hama þe we genemnan na cunnan. […] And hiom man raþe þas wið þingode, and hy namon frið.

[And they [the English] were put to flight there and many men were killed and the Danes had control of the place of slaughter; and the next day they [the Danes] burned the estates at Pinho and at Clyst and also many other good estates that we are unable to name. […] And negotiations were speedily held with them, and they made peace.] (pp. 170–71)

When the A-text resumes in the twelfth century with a few annals to 1070, there is a Norman on the throne.

Select Bibliography

Digitised Manuscript

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 173, fols 1–56. Parker Library on the Web https://parker.stanford.edu/parker. Accessed 15 November 2025.

Selected Editions and Translations of the A-text

Bately, Janet, ed. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. A Collaborative Edition, vol. 3, MS A (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1986).

Bately, Janet, ed., with Susan Irvine and Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe. The Old English Chronicle, volume 1, The A-Text to 1001. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2025).

Keynes, Simon, and Michael Lapidge, eds. Alfred the Great: Asser’s Life of King Alfred and other Contemporary Sources (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983).

Plummer, Charles, ed. Two of the Saxon Chronicles Parallel, with supplementary extracts from the others. A revised text … on the basis of an edition by John Earle. 2 vols (Oxford, 1892-1899; reissued with a bibliographical note by Dorothy Whitelock, 1952; repr. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972).

Swanton, Michael, ed. and trans. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (London: Dent, 1996).

Thorpe, Benjamin, ed. and trans. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 2 vols (London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1861).

Whitelock, Dorothy, with David Douglas and Susie I. Tucker, eds. and trans. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Revised Translation. 2nd corrected impression (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1965).

Studies and Criticism

Anlezark, Daniel. Constructing the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, Anglo-Saxon Studies 52 (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2025).

Bately, Janet. ‘The Compilation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 60 B.C. to A.D. 890: Vocabulary as Evidence’, Proceedings of the British Academy 1980 for 1978, pp. 93–129. Repr. British Academy Papers on Anglo-Saxon England, selected and introduced by E. G. Stanley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), pp. 261–97.

———. ‘Manuscript Layout and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 70 (1988), pp. 21-44; repr. in Textual and Material Culture in Anglo-Saxon England: Thomas Northcote Toller and the Toller Memorial Lectures, ed. Donald Scragg (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2003), pp. 1–21.

Clark, Cecily. ‘The Narrative Mode of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle before the Conquest’, in England before the Conquest: Studies in Primary Sources presented to Dorothy Whitelock, ed. Peter Clemoes and Kathleen Hughes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), pp. 215–35.

Dictionary of Old English: A to L online, ed. Angus Cameron, Ashley Crandell Amos, Antonette diPaolo Healey et al. (Toronto: Dictionary of Old English Project, 2024). <https://tapor.library.utoronto.ca/doe/>

Discenza, Nicole Guenther, and Paul E. Szarmach, eds. A Companion to Alfred the Great (Leiden: Brill, 2014).

Foot, Sarah. ‘Finding the Meaning of Form: Narrative in Annals and Chronicles’, in Writing Medieval History, ed. Nancy F. Partner (London: Hodder, Arnold, 2005), pp. 88–108.

Irvine, Susan. ‘The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’, in A Companion to Alfred the Great, ed. Nicole Guenther Discenza and Paul E. Szarmach (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 344–67.

Keynes, Simon. ‘Manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’, in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, Volume 1 c. 400–1100, ed. Richard Gameson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 537–52.

———. ‘Alfred the Great and the Kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons’, in A Companion to Alfred the Great, ed. Nicole Guenther Discenza and Paul E. Szarmach (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 13–46.

Lapidge, Michael, John Blair, Simon Keynes, and Donald Scragg, eds. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, 2nd ed. (Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2014).

Leneghan, Francis. ‘Royal Wisdom and the Alfredian Context of Cynewulf and Cyneheard’, Anglo-Saxon England 39 (2011), 71–104.

Pratt, David. The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Reuter, Timothy, ed. Alfred the Great, Papers from the Eleventh-Centenary Conferences (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2003).

Yorke, Barbara. ‘The Representation of Early West Saxon History in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’, in Reading the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Language, Literature, History, ed. Alice Jorgensen (Turnhout: Brepols, 2010), pp. 142–59.

About the author

Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe is Clyde and Evelyn Slusser Professor of English emerita, University of California, Berkeley.