Hagiography is not so much a literary genre as part of a cultural tradition, which includes calendars, litanies, martyrologies and legendaries, as well as independently circulating stories of the saints. Ælfric of Eynsham’s third collection, the so-called Lives of Saints (a title given by the nineteenth-century editor, William Walter Skeat, and not attested in any medieval manuscript), appears to have been modelled on the monastic legendary, but without the typical references to the day on which the pieces were to be read. Instead, it is thought that this collection was intended for private devotions, although it could also be read aloud for the benefit of both the literate and illiterate. The only complete manuscript of the Lives, London, British Library, Cotton Julius E.vii, begins its commemoration of the liturgical year on 25th December with two texts. The first is a prose homily ostensibly on the Nativity of Christ, although much of its subject matter is concerned with trinitarian theology and the nature of God. The second is an account of the martyrdom of St Eugenia written in Ælfric’s distinctive rhythmical prose. The commemoration of Eugenia on this date is unusual and witnessed only in this collection and in the Latin Cotton-Corpus legendary, a version of which is thought to have been the source from which Ælfric drew much of the material for his Lives. The liturgical calendars surviving from this period record the feast of St Eugenia on either 16th March or 16th May.

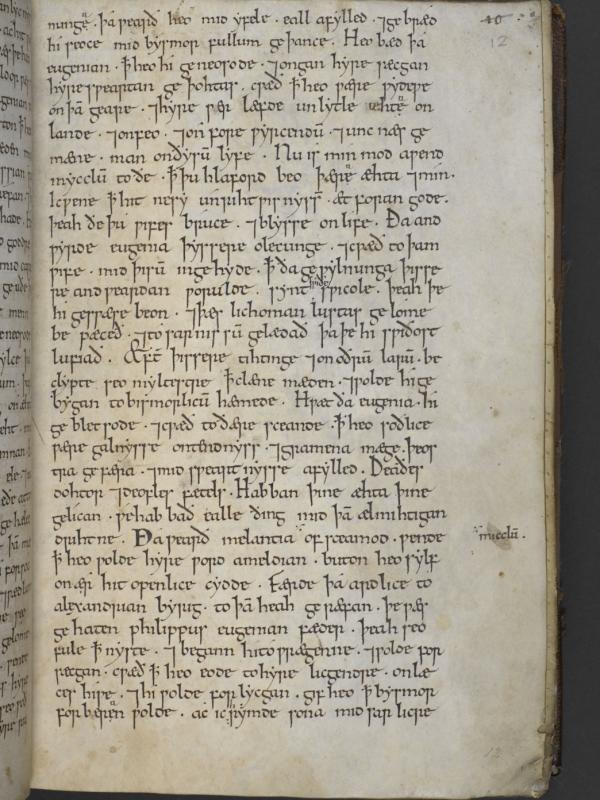

Two manuscripts preserve Ælfric’s passion of St Eugenia: London, British Library, Cotton Julius E.vii and London, British Library, Cotton Otho B.x, both conventionally dated to the first half of the eleventh century.

The Otho B.x manuscript was badly damaged as a result of the Cotton fire in 1731, however, and much of it is now illegible.

The version in Julius E.vii opens with an appeal to anyone who wishes to hear about Eugenia:

hu heo ðurh mægðhad mærlice þeah

and þurh martyrdome þisne middaneard oferswað.

(Eugenia, ll. 3–4)

[how she flourished gloriously by means of virginity

and overcame this world by martyrdom.]

The alliteration in these lines (marked in bold) links Eugenia’s celebrated virginity with her eventual martyrdom, her steadfast commitment to the former ultimately leading to the latter. From the very beginning, therefore, we see the importance of chastity to Ælfric’s conception of sanctity, both in his male and in his female subjects. As we shall see, Eugenia’s story is a particularly interesting examination of the challenges faced by the chaste, for she must preserve her purity both as a noble woman in Rome and as a cloistered man near Alexandria.

There is much about Eugenia’s biography which challenges narrow visions of ideal womanhood. Like many of her male counterparts in the Lives (such as Basil and Dionysius), Eugenia has been educated in Greek philosophy and Latin rhetoric (Greciscre uðwytegunge and Lædenre getingnysse, l. 21). This secular wisdom is only part of the saint’s achievement; in order to become truly learned she must receive the Christian teachings of St Paul. She travels from Alexandria in search of further education in Christian doctrine accompanied by two eunuchs, Protus and Hyacinth, who were also highly educated. Ælfric passes no comment upon the eunuchs, except to explain that such men are belisnode (‘castrated’, l. 46), although it is likely that he knew about eunuchs and their association with chastity from early Christian commentators such as Jerome. Eugenia approaches the Christians disguised as a man, but the bishop Helenus has been foretold in a dream the traveller’s true identity and warns her that she will suffer severe persecution for the sake of her virginity. This is one of a number of echoes that occur throughout the text, as the bishop’s words repeat the opening emphasis upon mægðhad and martyrdome (‘virginity’ and ‘martyrdom’, ll. 3–4).

Eugenia enters a monastery at the advice of the bishop, where she maintains her disguise ‘with a masculine spirit although she was a young woman’ (mid wærlicum mode, þeah þe heo mæden wære, l. 93). In these lines, and indeed throughout the narrative, Ælfric is insistent that the saint remains a woman, despite outward appearances. In this respect, her story contrasts with that of another transvestite saint, Euphrosyne, whose Life is also recorded in Cotton Julius E.vii and at one time attributed to Ælfric. For once she has adopted the clothing of a monk and claimed to be a eunuch, Euphrosnye is referred to using masculine pronouns, until she meets her father again. Ælfric avoids such a complete transformation, insisting that Eugenia remains a woman and is simply disguised as a man. This is particularly striking in the section of the story concerned with Melantia, who is healed by Eugenia (now an abbot) and tries to tempt her with treasures as a reward:

Þa wæs sum wif, wælig on æhtum,

Melantia gecyged, swiðe þearle gedreht

mid langsumum feofore, and com to ðære femnan.

(Eugenia, ll. 133–35)

[Then a woman, wealthy in possessions,

Melantia by name, was very badly afflicted

with a long-lasting fever, and she came to the virgin.]

In the Cotton Julius E.vii version of the account, the saint is referred to as ðære femnan (‘the woman’, l. 135), Eugenia (ll. 136, 153, 163, 172), þam mædene (‘the virgin’, l.141) and using the pronoun heo (‘she’, l. 153). It is therefore clear to the reader or listener that despite her disguise, she remains a woman. In the Cotton Otho B.x account, by contrast, the saint is referred to at the same points as þam abbude (‘the abbot’, ll. 135, 141), Se abbod (‘the abbot’, ll. 136, 163, 172), þone abbod (‘the abbot’, l. 153) and using the pronoun he (‘he’, l. 153). The unusual readings in Otho B.x continue into the scene where Eugenia is brought before the judge, who is in fact her father, Philip, and accused of trying to rape Melantia by pretending to be a doctor. The prefect does not recognise his daughter and responds to her with the anger typical of the tyrants found throughout Ælfric’s Lives:

Ða cwæð Philippus mid fullum graman

to Eugenian, his agenre dehter:

“Sege, þu forscyldeguda, hwi woldest ðu beswican

þæt mære wif Melantian mid forligre

and on læces hiwe hi forlicgan woldest?””

(Eugenia, ll. 200–04)

[Then Philip, full of rage,

said to Eugenia, his own daughter:

“Tell us, you wicked man, why did you desire to betray

that distinguished woman, Melantia, through fornication

and desire to lie with her in the guise of a doctor?”]

The irony of this scene lies in the fact that, of course, Melantia is not a distinguished or good woman (mære wif), just as the accused is not a wicked man (forscyldeguda), and the whole situation is only made possible because of Eugenia’s successful disguise (picked up in the word hiwe, l. 204). In the Otho B.x version, the insistence upon calling Eugenia an abbot further complicates the layers of deception, for Philip speaks in anger to þam abbode þe wæs his agen dohtor and he þæt niste (‘to the abbot who was his own daughter and he did not know it’, l. 201).

Eugenia’s response to these accusations represents the climax of this story and is arguably more dramatic than her eventual martyrdom. For she explains that she had dressed as a man so as to preserve her purity for Christ (Criste anum hyre clænnysse healdan, l. 230), then tears apart her clothes to reveal her breast to her father:

Æfter þysum wordum heo totær hyre gewædu

and ætæwde hyre breost þam breman Philippe

(Eugenia, ll. 234–35)

[After these words she tore apart her clothes

and revealed her breast to the illustrious Philip.]

In the Latin versions of the story, the saint then covers herself up modestly; this is not explicitly the case in Ælfric’s version, however. Instead, she is dressed in gold against her will (recalling the golden image her pagan parents constructed when they first lost Eugenia to the Christians) and her family and the people who had come to witness the trial converted by her example. Her father Philip’s conversion in many ways mirrors that of his daughter: he gives away his possessions and is promoted within the Church (in his case, to a bishop) before being betrayed and struck down while at prayer. He is the first of many in this collection to depart this life through martyrdom to the living Lord (mid martyrdome siþþan gewat to ðam lifigendan Drihtne, ll. 309–10).

Philip is buried in the grounds of the monastery of nuns (mynecena mynster, l. 312) that Eugenia had founded and she and her mother move to Rome, where she inspires many women by her example to convert to Christianity and adopt a chaste life. Her mother, Claudia, brings widows to the faith and the two eunuchs, Protus and Hyacinth, are also responsible for the conversion of young men to Christianity. When a noble Roman called Pompeius is rejected by his bride to be, Basilla, who has been inspired to the Christian life by Eugenia, he falls at the feet of the emperor and demands that the Christians be punished. Protus and Hyacinth are beheaded for refusing to sacrifice to the Roman idols and Eugenia endures a catalogue of tortures but is saved in every instance until eventually an executioner successfully kills her. She is buried a martyr on the day of Christ’s birth (on Cristes akennednysse dæge, l. 413). A single posthumous miracle is described—with a few notable exceptions, Ælfric typically avoids describing the cult of saints at their tombs—in which Eugenia appears to her mother, again dressed in gold, and comforts Claudia with a prophecy that she will join her husband and daughter among the blessed that Sunday. In this way, Ælfric adopts traditional tropes and motifs to bring to a close the passion of a saint who is in many ways non-traditional.

Select Bibliography

Editions and Translations

Clayton, Mary, and Juliet Mullins, ed. and trans. Old English Lives of Saints, Vols I–III: Ælfric, III, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 60 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

Donovan, Leslie A., trans. Women Saints’ Lives in Old English Prose, Library of Medieval Women (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1999).

Moloney, Bernadette. ‘A Critical Edition of Ælfric’s Virgin-Martyr Stories from The Lives of Saints’, unpublished doctoral thesis (University of Exeter, 1980).

Skeat, Walter W., ed. and trans. Ælfric’s Lives of Saints, EETS O. S. 76, 82, 94, 114 (London, 1881–90; repr. as 2 vols, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966).

Criticism

Jackson, Peter and Michael Lapidge. ‘The Contents of the Cotton-Corpus Legendary’, in Holy Men and Holy Women: Old English Prose Saints´ Lives and Their Contexts, ed. Paul E. Szarmach (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1996), pp. 131–46.

Lapidge, Michael. ‘Ælfric’s Sanctorale’ in Holy Men and Holy Women: Old English Prose Saints’ Lives and Their Contexts, ed. Paul E. Szarmach (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1996), pp. 115–29.

Lee, Stuart D. ‘Two Fragments from Cotton MS. Otho B. x’, British Library Journal 17.1 (1991), 83–87.

McDaniel, Rhonda L. The Third Gender and Ælfric’s Lives of Saints, Richard Rawlinson Center Series (Kalmazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2018).

Ostacchini, Luisa. Translating Europe in Ælfric’s Lives of Saints (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024).

Roy, Gopa. ‘A Virgin Acts Manfully: Ælfric’s Life of St Eugenia and the Latin Versions’, Leeds Studies in English, n.s. 23, (1992), 1–27.

Szarmach, Paul. ‘Ælfric’s Women Saints: Eugenia’, in New Readings on Women in Old English Literature, ed. Helen Damico and Alexandra Hennessey Olsen (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1990), pp. 146–57.

———. ‘St. Euphrosyne: Holy Transvestite’, in Holy Men and Holy Women: Old English Prose Saints’ Lives and Their Contexts, ed. Paul E. Szarmach (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1996), pp. 353–65.

Szarmach, Paul E., ed. Writing Women Saints in Anglo-Saxon England (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013).

About the author

Juliet Mullins is an adjunct lecturer and assistant professor in the School of English, Drama and Film and a member of the Humanities Institute, University College, Dublin. She has published on both Early Irish and Old English material. She co-authored with Mary Clayton a new edition and translation of Ælfric’s Lives of Saints for the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library.