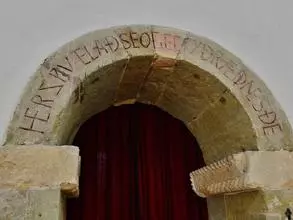

Inscription on porticus of St Mary's Church, Breamore, Hampshire (late tenth century): HER SWUTELAÐ SEO GECYDRÆDNES ÐE ['Here is manifested the covenant to you']

Over 200 vernacular texts inscribed on to artefacts or monuments span the period from the fifth century to the twelfth. They illustrate the development of English from its West Germanic roots, and concurrently represent the history of literacy in society, significantly complementing the manuscript record. They reveal, for instance, a high level of output in the eighth and ninth centuries; they are also valuable evidence for areas that otherwise have no surviving written evidence for Old English.

The earliest inscriptions are all in the runic script, using an evolving ‘Anglo-Saxon fuþorc’. This script remained in regular use for inscriptions in the vernacular down to the late ninth century, when it was abruptly discontinued except in educated, ecclesiastical contexts. Scandinavian influence of the Viking Period introduced a different ‘Younger fuþąrk’ runic script, usually for inscriptions in Old Norse although occasionally for Old and even early Middle English.

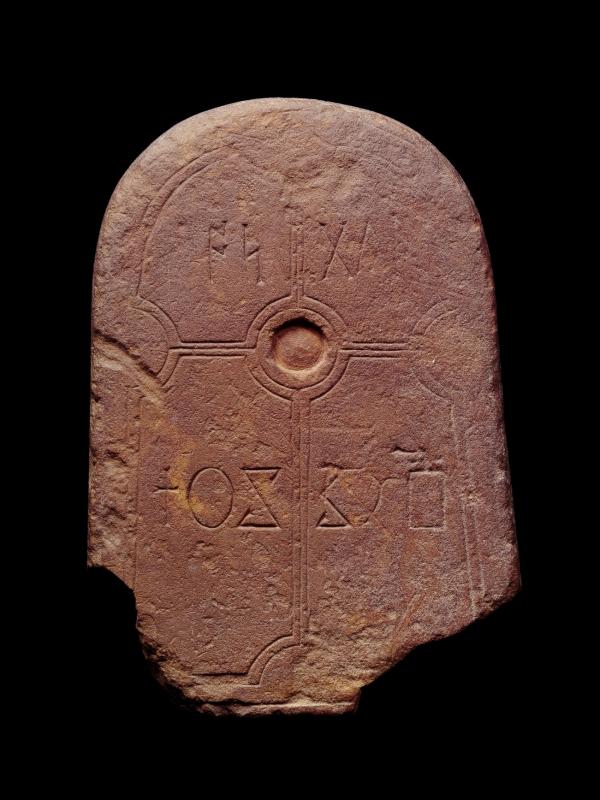

Chronologically in parallel with manuscript evidence, inscriptions (which can also be called ‘epigraphy’) testify to the use of the roman script — our own familiar alphabet — for both English and Latin, starting in the late seventh century. Up until the late eighth century, however, what we may classify as the Old English vernacular in roman script is restricted to personal names. There are several examples of the same name being written twice on a memorial namestone, using the two scripts in parallel.

This changed in Northumbria around the end of the eighth century with the adoption of a memorial formula that occurs on stone monuments in either script. It is represented in runes at Thornhill, West Yorkshire: +Gilswiþ ārǣrde æfter Berhtswīþe bēcun an bergi, gebiddaþ þǣr saule, ‘Gilswith raised after Berhtswith [this] monument on [a] hill, pray for that soul.’ The reference to the hill creates quadruple alliteration on b but not in a true metrical verse. The fullest roman-script counterpart is from nearby Dewsbury, also with alliteration of bēcun and the deceased man’s name, Beorn. The earliest known example of the ‘pray for that soul’ formula is on a stone cross at Bewcastle, Cumbria, where the individual commemorated may be a woman, Cyniburg, named on the face adjacent to these words. An equivalent formula appears in contemporary Latin inscriptions in this region: Orate pro anima…, ‘Pray for [the] soul’. It was presumably modelled on the Gregorian Litany of the Saints, which repeats the imperative Orate pro nobis, ‘Pray for us’.

The introduction of memorial inscriptions, alongside stone architecture and sculpture, followed the consolidation of the English Church in the later seventh century. Epigraphy on stone then continued strongly through to the Norman Period. The principal runic inscription on the Ruthwell Cross, Dumfries and Galloway, is in Old English verse surrounding symbolic vine-scroll ornamentation while the other two faces of the squared cross-shaft have Christian scenes with Latin prose captions or tituli. The only vernacular titulus we have is from Ipswich, a stone plaque portraying St Michael battling a dragon, which is so similar in design to the Bayeux Tapestry that it can be attributed to the later eleventh century.

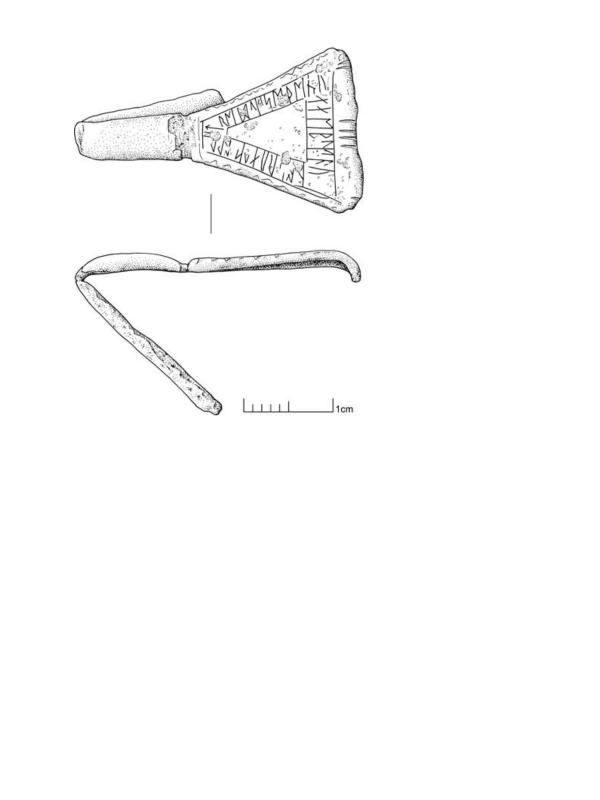

Throughout the Anglo-Saxon Period from the fifth century to the mid-eleventh, however, vernacular inscriptions are also found on portable objects. These were often gender-specific personal items, such as weaponry for men and brooches or pins from women’s costume, although there are many inscribed finger-rings with names that indicate those were worn by both sexes. A seax from Sittingbourne ostentatiously displays who owns the knife and who made it, but does so as an early example of a remarkable late ninth-century shift in how the inscribed object was ‘pointed to’. The demonstrative ‘this’ was replaced by the personal pronoun ‘me’, as if the item itself were using direct speech.

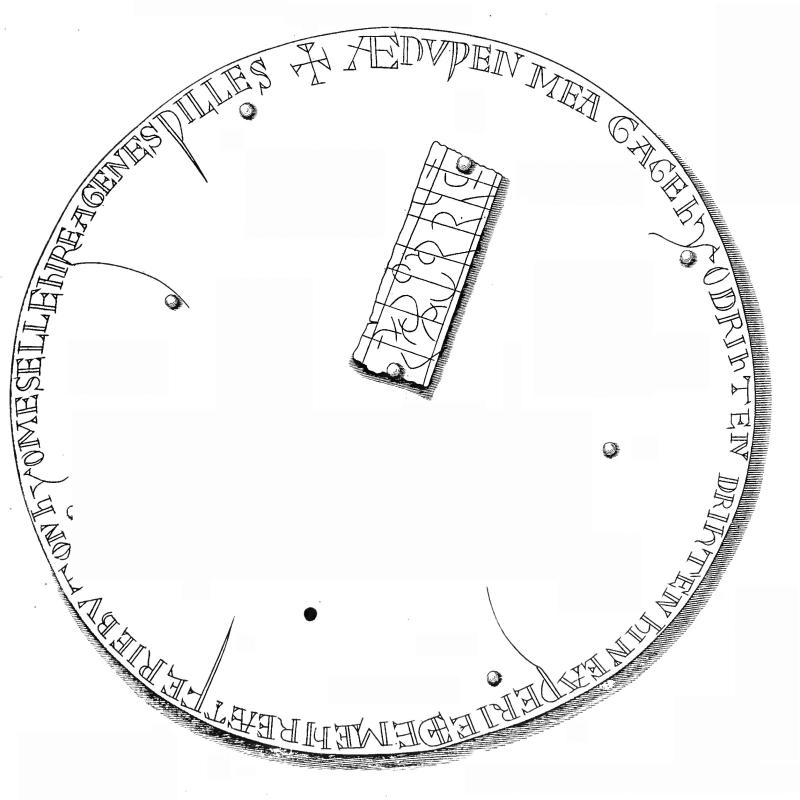

It must reflect a deep change in how people conceptualized their relationship with material artefacts that, at the same time, ‘ownership’ inscriptions largely superseded inscriptions recording who had made, commissioned or inscribed an item. In many cases those who ‘possessed’ the object were women. An outstanding example is a silver disc brooch from Sutton, Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire, with three lines of verse framing the back: the first in perfect alliterative metre, the other two with internal rhyme.

Real literary art in epigraphy is not restricted to verse. An inscription apparently of the late eighth century from Baconsthorpe, Norfolk, may appear mundane: ‘Read whoso may. Beaw inscribed these runes’. But its rǣdę se þe cynne is closely matched in the Riddles — secge se þe cunne/rǣde se þe wille, ‘say whoso can/interpret whoso will’ — and in characteristic verbal tics of Wulfstan’s homilies: gecnawe se þe cunne/understonde se þe cunne, ‘know/understand whoso can’. This inscription also illustrates how English adopted the verbs which give us read and write from vocabulary that was first used specifically for runic literacy.

The inscribed object from Baconsthorpe may have been a page-holder, a practical aid for reading. A brief runic inscription ‘[I] grew on a wild animal…’ was cut into an antler tine adapted as an ink-holder found at Brandon, Suffolk, and is similarly reminiscent of riddling style. Most inscriptions are individualizing identifications that belong to a single, specific context; that is a key difference from the expansive texts of fully literary prose which in theory could be reproduced in identical multiple copies. The contemporary multi-media concept of ‘transmateriality’ might be employed here better to appreciate the continuum between epigraphy — which historically was truly primary — and literature. In the late ninth century, King Alfred remembered how ‘many people used to be able to read written English.’ Inscriptions are the form in which the written vernacular would have been most widely seen. They draw attention to how syntax had to be managed and show how styles developed. Thus they form a valuable complement to more conventional Old English literary studies.

Select Bibliography

Hines, John. ‘New light on literacy in eighth-century East Anglia: a runic inscription from Baconsthorpe, Norfolk’. Anglia129 (2011), 281–96.

———. ‘The Benedicite canticle in Old English verse: an early runic witness from southern Lincolnshire’. Anglia 133 (2015), 257–77.

———. ‘The Ruthwell Cross, the Brussels Cross and The Dream of the Rood.’ In G. D. Caie and M. D. C. Drout (eds), Transitional States: Change, Tradition, and Memory in Medieval Literature and Culture (University of Arizona Press, 2018), 175–92.

———. ‘Practical runic literacy in the Late Anglo-Saxon Period: inscriptions on lead sheet’. In U. Lenker and L. Kornexl (eds), Anglo-Saxon Micro-Texts (De Gruyter, 2019), 29–60.

———. ‘New insights into Early Old English from recent Anglo-Saxon runic finds’. NOWELE 73 (2020), 69–90.

———. ‘The dark side of the runes’. In S. Pink and A. J. Lappin (eds), Dark Archives Vol. I: Voyages into the Medieval Unread & Unreadable 2019–2021 (Medium Ævum Monographs 43, 2022), 97–124.

———. ‘The evolution of a definite article in Old English: evidence from a filiation formula in a runic inscription from Eyke, Suffolk’. Anglia 142 (2024), 683–712.

Okasha, Elisabeth. Hand-list of Anglo-Saxon Non-Runic Inscriptions (Cambridge University Press, 1971).

Elisabeth Okasha has published four ‘Supplements’ to this volume in the journal Anglo-Saxon England: Volume 11 (1983), pp 83–118 (https://doi.org/10.1017/S026367510000257X); Volume 21 1992) pp 37–85 (https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263675100004178); Volume 33 (2004), pp 225–81 (https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263675104000080); Volume 47 (2020), pp 365–423 (https://doi.org/10.1017/S02636751190001150). She is currently working on a Fifth Supplement.

Page, Ray I. An Introduction to English Runes 2nd ed (Boydell Press, 1999).

Waxenberger, Gaby, Kerstin Kazazzi and John Hines (eds). Old English Runes: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Approaches and Methodologies with a Concise and Selected Guide to Terminologies (De Gruyter, 2023).

About the author

John Hines is Professor emeritus of Archaeology from Cardiff University where he was previously Reader in English. His research and teaching lay in multidisciplinary approaches to knowledge and understanding of northern Europe across the last two millennia. He was the founding General Editor of Boydell & Brewer’s monograph series Anglo-Saxon Studies and is a former editor of Medieval Archaeology. He is currently Vice-President of the Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature (Medium Ævum) and also served as President of the Viking Society for Northern Research and Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

Figure credits

Figure 1. © DigVentures and Durham University. Reproduced by kind permission.

Figure 2. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Figure 3. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Figure 4. Engraving published in George Hickes, Linguarum Vett. Septentrionalium Thesaurus Grammatic-Criticus et Archæologicus (Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, 1705), p 186.

Figure 5. Drawing by David Dobson, NAU Archaeology.