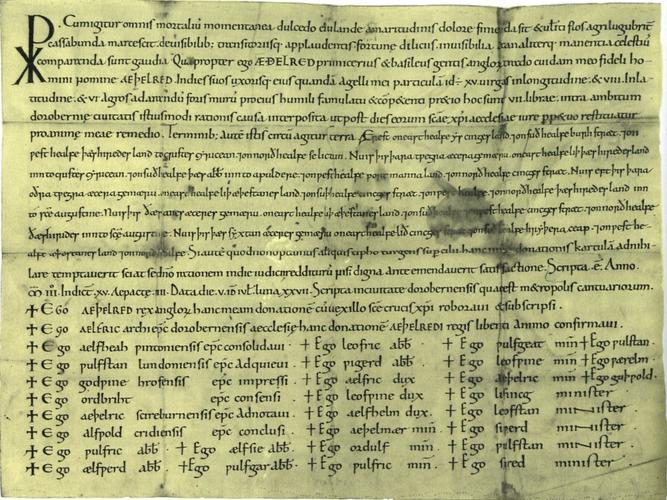

Although over 1500 charters date (or claim to date) from the pre-Conquest period, most are Latin diplomas, royal grants of land to religious foundations or individuals. Only about a fifth of these survive in anything like original, single-sheet, form. Many of the rest owe their preservation to their inclusion in cartularies (collections of charters) compiled by religious foundations, most of which date from the thirteenth through to the fifteenth century. ‘Charter’ is the umbrella term generally used for most kinds of document produced during this period.

Diplomas

Diplomas, the earliest of which dates from the beginning of the seventh century, form by far the largest subset of charters issued in the period. Boundary clauses, outlining the geographical extent of the estate granted, appear first in diplomas from about AD 700, containing Old English terms housed within Latin compass directions. A more extensive boundary clause, completely in the vernacular, is predominant by the beginning of the tenth century. Around eight hundred sets survive, providing important evidence for topographical terms, some of which show interesting dialectal variation. A typical structure identifies the boundaries of the estate on a circuit through a series of landscape features along the route such as water-courses, trees, hedges, settlements and other abutting estates. Some boundaries can still be traced today.

Non-literary documents written entirely in Old English number about 300 in total. While varied in nature, as discussed below, there are significant numbers of certain text types, including writs, leases and wills.

Writs

A vernacular text-type, writs are essentially sealed administrative letters comprising orders or notifications, such as confirmation or grants of liberties, appointments to office, or transfer of land. Over 120 of these survive. Most are royal, dating from the reign of Edward the Confessor (1042–1066). The form seems to date at least as far back as the reign of King Alfred (871–899)—an inserted passage in the Alfredian translation of the Soliloquies mentions a lord’s writ and seal—although none survives from that period.

Leases

Over 100 leases survive, in which religious houses granted land to tenants for their lifetime and often that of one or two named successors. Few are written entirely in Old English. However, like the diploma, most leases include a vernacular boundary clause; around a quarter additionally include some kind of summary in Old English.

Wills

Over sixty wills and bequests survive. They are generally those of important people, royalty (including Kings Eadred and Alfred), ealdormen and leading ecclesiastics, but their number includes those who cannot be traced elsewhere. A significant proportion are by women. A few Latin-only survivals are likely post-Conquest summaries of vernacular originals. Witness-lists or boundary clauses are uncommon in this text type. Several of the wills are lengthy and provide rich detail of both personal and landed property, familial relationships, and evidence of naming practices down the social scale. The following extract is from the beginning of Æthelflæd’s will (Sawyer 1494), which survives alongside that of her younger sister and father. Æthelflæd was married to Ealdorman Byrhtnoth, of The Battle of Maldon fame; the will predates his death in 991. The ‘lord’ referred to here is the king. The text and translation are mine, with punctuation modernised:

Þis is Æþelflede cwyde. Þæt is ærest þæt ic gean minum hlaforde þes landes æt Lamburnan 7 þæs æt Ceolsige 7 æt Readingan 7 feower beagas on twam hund mancys goldes, 7 .iiii. pellas 7 .iiii. cuppan 7 .iiii. bleda 7 .iiii. hors. 7 ic bidde minne leouan hlaford for Godes lufun þæt min cwyde standan mote, 7 ic nan oðer nebbe geworht on Godes gewitnesse.

[This is Æthelflæd’s will. That is first that I grant my lord the estate at Lambourn and that at Cholsey and at Reading, and four armlets worth two hundred mancuses of gold, and four cloaks, and four cups, and four vessels, and four horses. And I beseech my beloved lord for the love of God that my will be allowed to stand, and I have made no other, as God is my witness.]

Other texts

Other surviving vernacular documents vary widely, including booklists, records of legal disputes, memoranda, inventories, funerary arrangements, manumissions (freeing slaves), and agreements. Some cannot be reliably dated and may post-date the Conquest. Many are ephemeral in nature, and survive by happenstance, after being redeployed as flyleaves to a later binding. The longevity of others was more assured as they were copied into important service books to avoid being lost.

The following extract is from a tenth-century record (Sawyer 1449) which recounts the legal wrangling over two estates in unusual detail. It begins by narrating the theft of a woman, and the subsequent failure of one Æthelstan, tasked to take the matter on, to attend the hearing. His failure incurred a fine of the sum of his wergeld (a legally-fixed value of an individual’s life). Æthelstan is unable to pay. Here text and translation (with punctuation modernised) is by Robertson:

Þa cwæð Æðelstan þæt he næfde him to syllanne. Þa cleopode Eadweard Æðelstanes broðor 7 cwæð: ‘ic hæbbe Sunnanburges boc ðe uncre yldran me læfdon. Læt me þæt land to handa ic agife þinne wer ðam cynge’. Þa cwæð Æðelstan þæt him leofre wære þæt hit to fyre oððe flode gewurde þonne he hit æfre gebide. Ða cwæð Eadweard, ‘hit is wyrse þæt uncer naðor hit næbbe.’ Þa wæs þæt swa.

[Then Æthelstan said he had nothing to give him. Then Edward, Æthelstan’s brother spoke up and said, ‘I have the title-deeds of Sunbury which our parents left me; give me possession of the estate and I will pay your wergeld to the king.’ Then Æthelstan said that he would rather that it perished by fire or flood than suffer that. Then Edward said, ‘It would be worse for neither of us to have it.’ But that was what happened.]

As a whole, the corpus of vernacular charters and records contributes significantly to our understanding of documentary culture and the use of writing in administrative contexts in the pre-Conquest period.

Select Bibliography

Bibliography note

Charters are catalogued and listed in Sawyer 1968, now updated (reliably to 2000) and available online; it is usual to refer to Sawyer numbers to identify particular charters. A very useful, more up-to-date, tool is the ‘Languages of Anglo-Saxon Charters’ database at https://www.ehu.eus/lasc/ with bibliography.

The majority of diplomas were edited in the nineteenth century, but these editions are gradually being superseded by volumes in the British Academy/Royal Historical Anglo-Saxon Charters series (1966–), details here: https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/projects/academy-research-projects-anglo-saxon-charters/. Many vernacular texts which do not fall into the main categories listed above are not included in Sawyer, but are listed in the appendix to Lowe (2021). Post-Conquest vernacular documents are listed in Pelteret (1990).

Editions

Anglo-Saxon Charters, ed. and trans. Agnes J. Robertson, 2nd edn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1956).

Anglo-Saxon Wills, ed. and trans. Dorothy Whitelock (Cambridge: CUP, 1930).

Anglo-Saxon Writs, ed. and trans. Florence E. Harmer, 2nd edn (Stamford: Paul Watkins, 1989),

Pelteret, David A. E. Catalogue of English Post-Conquest Vernacular Documents (Woodbridge, 1990).

Sawyer, P. H. Anglo-Saxon Charters: An Annotated List and Bibliography (London: Royal Historical Society,1968), revised as the Electronic Sawyer, https://esawyer.lib.cam.ac.uk/about/about.html

Select English Historical Documents of the Ninth and Tenth Centuries, ed. and trans. Florence E. Harmer(Cambridge: CUP, 1914).

Criticism

Fenton, Albert. ‘Royal Authority, Regional Integriy: the Function and Use of Anglo-Saxon Writ Formulae’, in The Languages of Early Medieval Charters: Latin, Germanic Vernaculars and the Written Word, ed. by Robert Gallagher, Edward Roberts and Francesca Tinti (Leiden: Brill, 2021), pp. 412–39.

Gallagher, Robert. ‘The Vernacular in Anglo-Saxon Charters: Expansion and Innovation in Ninth-Century England’, Historical Research 91 (2018), 205–35.

Gallagher, Robert, and Francesca Tinti. ‘Latin, Old English and Documentary Practice at Worcester from Wærferth to Oswald’, Anglo-Saxon England 46 (2017), 271–325.

Lowe, Kathryn A. ‘“As Fre as Thowt?” Some Medieval Copies and Translations of Old English Wills’, English Manuscript Studies 1100–1700 4 (1993), 1–23.

———. ‘The Development of the Anglo‑Saxon Boundary Clause’, Nomina 21 (1998), 63–100.

———. ‘The Nature and Effect of the Anglo‑Saxon Vernacular Will’, Journal of Legal History 19 (1998), 23–61.

———. ‘From Memorandum to Written Record: Function and Formality in Old English Non-Literary Texts’, in The Languages of Early Medieval Charters: Latin, Germanic Vernaculars and the Written Word, ed. by Robert Gallagher, Edward Roberts and Francesca Tinti (Leiden: Brill, 2021), pp. 440–87.

Tinti, Francesca. ‘Writing Latin and Old English in Tenth‑Century England: Patterns, Formulae and Language Choice in the Leases of Oswald of Worcester’, in Rory Naismith and David A. Woodman (eds), Writing, Kingship and Power in Anglo‑Saxon England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 303–27.

Tollerton, Linda. Wills and Will-Making in Anglo-Saxon England (Woodbridge: York Medieval Press, 2011).

About the author

Kathryn Lowe is Senior Lecturer in Old and Middle English at the University of Glasgow. She has published extensively on non-literary texts, textual transmission, the history of scholarship, lay literacy and the transition between Old and Middle English.