For the year 793 CE, the D, E and F versions of the Anglo-Saxon or Old English Chronicles record a series of terrifying portents that include hæþenra manna hergunc (‘the harrowing of heathen men’) and signal the arrival of the Vikings in England:

Her wæron reðe forebecna cumene ofer Norðhymbra land, ⁊ þæt folc earmlic bregdon, þæt wæron ormete þodenas ligrescas, fyrenne dracan wæron gesewene on þam lifte fleogende. Þam tacnum sona fyligde mycel hunger, ⁊ litel æfter þam, þæs ilcan geares on .vi. Idus Ianuarii, earmlice hæþenra manna hergunc adilegode Godes cyrican in Lindisfarnaee þurh hreaflac mansliht.

[This year came dreadful forewarnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light, and fiery dragons were seen flying through the air. These signs were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God on Lindisfarne, by rapine and slaughter.]

This account is traditionally interpreted as one of the earliest records of Viking incursions into England, which were to continue in waves of varying intensity throughout the ninth and tenth centuries, until the ascension of the Danish king Cnut onto the English throne in 1016 CE.

In the A-version of the Old English Chronicles, also known as the Parker Chronicle, the struggles and victories that Alfred the Great (reigned 871–899 CE) and his son, Edward the Elder (899–924), experienced against the invading Scandinavian forces during the first Viking age are documented. Not all kings enjoyed military success, however. Ælla, king of Northumbria (d. 867CE), was killed fighting ‘the Great Heathen Army’ according to English sources; later Norse sagas claim that he died from the famous (and probably fictitious) blood eagle ritual, to which he was subjected in revenge for killing Ragnar Lodbrok. Another king to have died at the hands of the Vikings was Edmund, king of East Anglia (d. 869), who refused to yield to the demands of the invaders and was punished by being shot through with arrows and then beheaded. This king, known as the Edmund the Martyr, was the subject of both a Latin and an Old English Passion (an account of a martyr’s death) composed during the second Viking Age, at the end of the tenth century, and was venerated as the patron saint of England until he was replaced by St George in the fifteenth century.

Despite his importance as a native English saint, the introduction to Ælfric's Old English Passion of St Edmund places the commemoration of the East Anglian king within an international setting. This is one of only two Lives or Passions in Ælfric’s Lives of Saints to open with a prose introduction explaining the context of the work’s composition (the other is the Passion of St Thomas). In these opening lines, Ælfric indicates that the saint’s first hagiographer, Abbo of Fleury, ‘came over the sea from the south from St Benedict’s monastery’. The powerful social bonds created by memory and storytelling are introduced in the opening passage of this Passion, when Ælfric (following the Latin Passio composed by Abbo) describes the passing of the story of the king´s martyrdom from one generation to the next:

Sum swyðe gelæred munuc com suþan ofer sæ fram Sancte Benedictes stowe, on Æþelredes cynincges dæge, to Dunstane ærcebisceope, þrim gearum ær he forðferde, and se munuc hatte Abbo. Þa wurdon hi æt spræce oþþæt Dunstan rehte Æþelstane cynincge þa þa Dunstan iung man wæs and se swurdbora wæs forealdod man. Þa gesette se munuc ealle þa gereccednysse on anre bec, and eft ða þa seo boc com to us, binnan feawum gearum, þa awende we hit on Englisc swa swa hit heræfter stent. (Edmund 1)

[In the days of King Æthelred, a very learned monk came over the sea from the south from St Benedict’s monastery to Archbishop Dunstan, three years before he died, and the monk was called Abbo. They talked then until Dunstan told the story of Saint Edmund, just as Edmund’s sword-bearer had told it to King Æthelstan when Dunstan was a young man and the sword-bearer was a very old man. Then the monk recorded the whole story in a book, and afterward, within a few years, when the book came to us, we translated it into English just as it stands hereafter.]

The processes of memory creation and commemoration are placed within a regnal context: Abbo travelled to England on Æþelredes cynincges dæge (‘in the days of King Æthelred’) and the story passed orally from the sword-bearer to King Athelstan, then to Archbishop Dunstan, and finally to Abbo, before being committed to writing. Moreover, the Viking leader Hinguar begins his attack when Alfred, who would later be the famous king of the West Saxons, was 21 years old (Edmund 2:25-6). In this way, the West Saxon dynasty is integrated into the story of the East Anglian king, thereby ensuring their position within the sanctified community of memory.

Kingship and models of good and bad leadership are recurring themes of Ælfric’s Lives of Saints. Indeed, since the collection was composed for his high-ranking lay patrons, the West Saxon ealdorman Æthelweard and his son Æthelmaer, many of the texts could be read as a form of speculum principis (‘mirror for princes’). Both men were active in court life and were close to the king, Æthelred II (reigned 978–1013, 1014–1016). Indeed, in 994, at the request of the king, Æthelweard, together with another ealdorman also called Ælfric and the Archbishop Sigeric, negotiated a peace treaty with the Viking leader, Olaf Tryggvason. The peace was short lived, but it provides an interesting context for Ælfric’s portrayal of Edmund. For this Passion was one of the earliest pieces composed in the Lives of Saints collection (which was compiled during the period 993 x 998) and reflects a very different image of ideal leadership to that found in the Passion of St Oswald or in the Maccabees, for instance. For while Oswald is introduced as a military king engaged in battle within a few lines, Edmund is praised with a paraphrase of Ecclesiasticus 32:1:

[he] wæs symble gemyndig þære soþan lare:

“Þu eart to heafodmen geset? Ne ahefe þu ðe,

ac beo betwux mannum swa swa an man of him.”

(Edmund, 2:7–9)

[he was always mindful of the true doctrine:

“Are you appointed as a leader? Do not exalt yourself,

but be among people as one of them.’”]

Following this sentiment, it is notable that in the Passion of St Edmund, it is not only kings and high-ranking ecclesiasts who are involved in the process of promoting the legend of the saint; ordinary (albeit unnamed) people also play a seminal role. The martyrdom of St Edmund is witnessed not only by ‘the wicked men’ (þa areleasan) who bind and torture him, but also by a man of whom we know nothing save that through divine intervention he was hidden from the heathens:

Þær wæs sum man gehende, gehealden þurh God

behyd þam hæþenum, þe þis gehyrde eall

and hit eft sæde swa swa we hit secgað her.

(Edmund, 2:115–17)

[There was a man nearby, kept hidden by God

from the heathens, who heard all this

and reported it afterwards just as we tell it here.]

Once more, the passing of information by word of mouth is instrumental in the preservation of the saint’s memory. But in this instance, there is added dimension as this man is described a few lines later (2:126) as se sceawere (‘the witness’). On a narrative level, the role of this character is minimal; as already mentioned he is given no name and no description, nor he is given the opportunity to describe in his own words the events that he has observed. However, his presence at the torture scene provides a Christian interpretation of the events that unfurl and the occasion for the reader to gaze upon the beaten, tortured body of the saint who was shot through with arrows swa swa Sebastianus wæs (‘just as Sebastian was,’ Edmund, 2:106).

The reference to Sebastian is a reminder of the ways in which memories can be used to connect people and communities across time and illustrates the importance of the universal saints as models for native holy men and women. In other respects, however, Edmund’s story is unusual because it displays features more typical of romance and the type of motifs found in later popular hagiographical narratives. So, for instance, the Danish leader Hinguar (Ælfric typically labels all the Scandinavian invaders as ‘Danes’) is compared in his ferocity to a wolf:

And se foresæda Hinguar færlice swa swa wulf

on lande bestalcode and þa leode ofsloh

— weras and wif and þa unwittigan cild —

and to bysmore tucode þa bilewitan Cristenan.

(Edmund, 2:27–30)

[And the Hinguar that we mentioned before suddenly moved stealthily

onto the land like a wolf and killed the people

— men and women and innocent children —

and shamefully ill-treated innocent Christians.]

The Vikings are frequently compared to savage wolves in Old English literature, but the potency of the image is increased in this Passion because when the Vikings hide the decapitated head of the king (presumably to prevent a proper burial), a wolf is sent by God to protect it. Moreover, when the local people find the head—which calls out to them as they search through the forest—the wolf insists upon accompanying it to his place of burial:

Ac se wulf folgode forð mid þam heafde

oþþæt hi to tune common, swylce he tam wære,

and gewende eft siþþan to wuda ongean.

Þa landleoda þa siþþan ledon þæt heafod

to þam halgan bodige and bebyrigdon hine

swa swa hi selost mihton on swylcere hrædinge,

and cyrcan arærdan sona him onuppon.”

(Edmund 2:149–55)

[But the wolf accompanied the head

until they came to the town, as if it were tame,

and then turned back again to the wood.

Afterward the local people laid the head

beside the holy body and buried him

as best they could in such haste,

and erected a chapel over him immediately.]

Many years later, once the Viking raids have ceased, a larger church was built over the body of the saint and miracles were recorded at his tomb (Edmund, 2:156–61). These miracles involve the local nobility, the ecclesiastical hierarchy (in the person of Bishop Theodred) and the ordinary people. Generally speaking, Ælfric avoids describing the wonders performed at the tombs of the saints in this collection, focussing instead upon the virtutes demonstrated during the lifetime of the holy men and women. The exceptions are the native saints—Æthelthryth, Edmund, Oswald and Swithun—who perform no miracles during their lives (unless the preservation of Æthelthryth’s virginity through two marriages is considered miraculous); instead, they demonstrate the continuation of divine intervention in the lives of the ordinary people who attend the shrine. That memories continue to circulate concerning the saint and his posthumous powers is acknowledged by Ælfric when he admits that:

Fela wundra we gehyrdon on folclicre spræce

be þam halgan Eadmunde þe we her nellaþ

on gewrite settan, ac hi wat gehwa.

(Edmund, 2:235–37)

[We have heard of many miracles in common talk

about St Edmund that we will not set down

in writing here, but everyone knows them.]

In the versions of the Passion preserved in the manuscripts Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 343 (B), Cambridge, University Library I.i.i.33 (L) and possibly in London, BL, Cotton Vitellius D.xvii (fᵏ), this acknowledgement is followed by the claim that:

Wyrðe wære seo stow for þam wurðfullan halgan

þæt hi man wurþode and wel gelogode

mid clænum Godes þeowum to Cristes þeowdome

forþan þe se halga is mærra þonne men magon asmeagan.

(Edmund, 2:243–46)

[For the sake of the venerable saint, the place

is worthy of being honoured and well provided

with God's chaste servants for Christ´s service

because the saint is greater than people can imagine.]

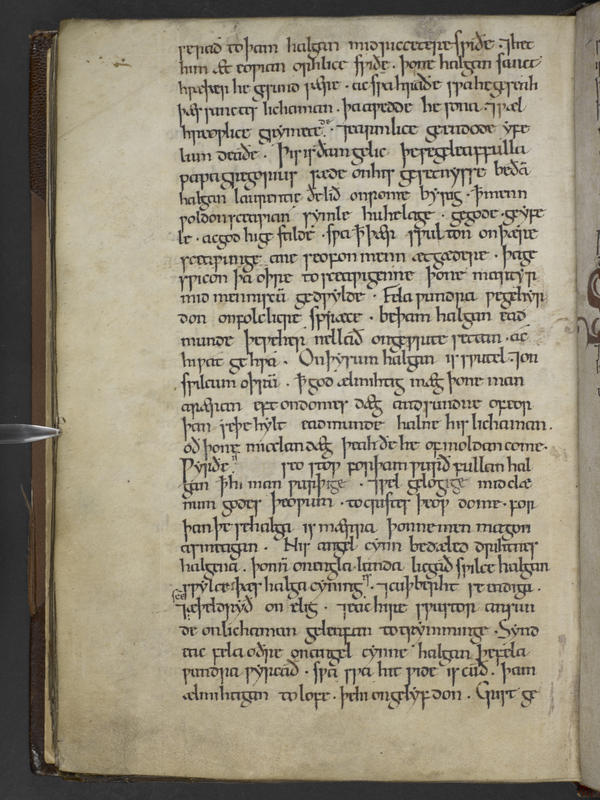

In these manuscripts, the preterite subjunctive is used to express the need to realise proper action: this is what should be done. In Cotton Julius E.vii, however, a contemporary corrector has intervened so that wære has been replaced with is, wurþode with wurþige and gelogode with gelogige, thus placing the action into the present tense (see Fig.1):

Wyrðe is seo stow for þam wurðfullan halgan

þæt hi man wurþige and wel gelogige

mid clænum Godes þeowum to Cristes þeowdome

forþan þe se halga is mærra þonne men magon asmeagan.

(Edmund, 2:243–46)

These changes are made over erasures in a contemporary hand by the scribe whose corrections are characterised by two points or a colon (and who we refer to therefore as ‘the points corrector’). Although perhaps insubstantial at a grammatical level, the changes to this passage reflect part of a broader programme of memory creation surrounding St Edmund that continued long after Ælfric’s death. And, depending on how we date Cotton Julius E.vii and the work of the points corrector, these changes may represent part of a movement to use the memory of Edmund’s death to create a new, Anglo-Scandinavian community under the patronage of Cnut.

Select Bibliography

Editions and Translations

Clayton, Mary, and Juliet Mullins, ed. and trans. Old English Lives of Saints, Vol. I–III: Ælfric, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 60 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

Hervey, Lord Francis, ed. and trans. Corolla Sancti Eadmundi: The Garland of St Edmund [Latin] (London, 1907).

Needham, G.I., ed. Ælfric: Lives of Three English Saints (London: Methuen, 1966; repr. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1992).

Skeat, Walter W., ed. and trans. Ælfric’s Lives of Saints, EETS O. S. 76, 82, 94, 114 (London, 1881-90; repr. as 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966).

Winterbottom, Michael., ed. Three Lives of English Saints [Latin] (Toronto: Toronto University Press, 1972).

Criticism

Cesario, Marilina. ‘Fyrenne Dracan in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’, in Textiles, Text, Intertext: Essays in Honour of Gale R. Owen-Crocker, ed. Maren Clegg Hyer (Cambridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2016), pp. 153–70.

Clayton, Mary. ‘Ælfric and Æthelred’, in Essays on Anglo-Saxon and Related Themes in Memory of Lynne Grundy, ed. Jane Roberts and Janet Nelson (London: King’s College London Centre for Late Antique and Medieval Studies, 2000), pp. 65–88.

Frank, Roberta. ‘Viking atrocity and skaldic verse: the rite of the blood eagle’, English Historical Review 99 (1984), 332–43.

Needham, Geoffrey. ‘Additions and Alterations in Cotton MS Julius E VII’, The Review of English Studies, ns, Vol. 9, No. 34 (1958), 160–64.

North, Richard and Joe Allard, ed. Beowulf and Other Stories: A New Introduction to Old English, Old Icelandic and Anglo-Norman Literatures (London: Pearson Education, 2007).

Parker, Eleanor. Dragon Lords: The History and Legends of Viking England (London: Bloomsbury, 2021).

Rollason, David. ‘Relic Cults as an Instrument of Royal Policy c.900-c.1050’, Anglo-Saxon England 15 (1986), 91–103.

About the author

Juliet Mullins is an adjunct lecturer and assistant professor in the School of English, Drama and Film and a member of the Humanities Institute, University College, Dublin. She has published on both Early Irish and Old English material. She co-authored with Mary Clayton a new edition and translation of Ælfric’s Lives of Saintsfor the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library.